The teaching profession is shifting and more and more of us are taking on split or hybrid roles where part of the day is in the classroom and part is spent coaching or writing curriculum. So what do you do when you have to 1) share your room with a colleague and 2) hold classes in the library because that is the only available space? I am so pleased today to share the multi-functional classroom of my dear friend Melissa Barkin Scheinfeld. Melissa and I were in the same collaborative group at our pre-service teaching institute in 2005 and have been friends ever since. Whenever I have a particularly tricky teaching situation or just need a really brilliant thought partner I ring up Melissa. It is no surprise to see what an amazing classroom she has made despite some logistical challenges. Thank you for sharing your classroom Melissa!

Where do you teach? I teach in Austin, Texas at KIPP Austin Collegiate. We are the only KIPP high school in Austin.Who are your students? My students are seniors who are currently applying to college and getting ready to take over the world. They are brimming with personality and we will be in good hands when they are the ones making decisions for this city. The majority of them come from Hispanic, low-income backgrounds and they have been KIPPsters since anywhere from 5th to 9th grade.

What do you teach? I teach Government and Economics. This is my first year teaching this course after a long stint in World Geography and AP World History. I am loving the opportunity to write new curriculum and teach Political Science.

The white board floating at the front of the room is on wheels and the English teacher and I rotate it depending on whose class is being taught. For additional writing space, there are packets of poster paper attached to it with binder clips. When there is additional information I want in front of my students, I put it on the chart paper and flip back and forth in the stack to get to the key info. It can be a bit of a challenge as it all adds a few more tasks in order to get set up for class, but for the most part it’s working great this year.

I have a filing cabinet in my classroom for students to pick up anything they are missing. The sign above it says, “Your GPA tells a story about you…what story do you want to tell? Check your grades and pick up missing work here.” The key to this system is that I don’t have to be around for a student to figure out what he/she needs to do to improve their grade or to help him/her find the missing/replacement handouts to get organized. Every teacher in my building has a system like this and we all know that if we’re supporting a student, we can send the student to another room to find extra copies of the assignment that needs additional attention.

There are two signs that I’ve had up in my room every year since Abby gave me the brilliant idea… “This is my Dream Job. What’s yours?” and “Yes, I really do love you.” It’s incredible how many times students have referenced these two signs when I talk to them about our class years later. They are very empowering messages. And, I love to shamelessly promote careers related to the class I’m teaching, so the rest of the wall includes a list of jobs that this class might lead toward.

Describe your teaching style in one word. Disciplined

What is your go-to literacy strategy? I am a very strong proponent of peer revision in my classroom as a way for students to improve their writing skills. My go-to strategy (which I, of course, learned from fantastic colleague several years ago) is called “clocking.” I’m not sure where she got the name for it, but it stuck. It’s basically speed dating for essay revision. It requires three planning details:

1. Clocking worksheet: I give students a document with 5 text boxes, each labeled with a different area from their essay rubric. Each section has a title (straight from the rubric) and a place for the “reviser” to write his/her name. In each box there are two sections, one for “This is what you wrote…” and the other, “I think it should be…”

2. Seating arrangement: I move students into two long rows, or an inner circle or an outer circle, depending on the shape of the room. The key is that each kid is sitting across from another student and they have a table in between them to work. After each round, one of the circles or rows stands up and rotates. Each student then has a new partner and a fresh set of eyes on his/her paper.

3. Mini-lessons: I do a quick mini-lesson with strong and weak student examples at the beginning of each round. When students are facing their first partner, I model feedback for the first skill (i.e. thesis statement, citations, claim and evidence in every paragraph, spelling, etc.) by revising 1-3 student examples that are almost perfect, if they just had one more piece of feedback. Often I make them up myself because I haven’t read everyone’s rough draft. The ideal examples are those that are mostly strong, but need one piece of clear, specific feedback to improve. I try to bring samples of the most common student mistakes so students can see a model both for how to write well and how to give good feedback. Students then pass both their essay and their “clocking worksheet” to their partner. Each has 5 minutes silently to give feedback on the worksheet, then they have 3 minutes to explain their feedback out loud. After eight minutes, one of the rows rotates, I give a new mini-lesson, and student trade papers with the new partner.

One of my students e-mailed me this picture last week for us to use on future “clocking worksheets.” Obviously it’s intended for scientific research, but I like his interpretation of it for our Social Studies essays.

How do you motivate your students? Every single thing we do in class is tied to a college-readiness skill. Students’ grades are based 100% on their demonstration of that skill by the end of the semester. I’m experimenting this year with this policy of “standards-based grading” and finding it to be an incredible motivator. I learned an anecdote a few years ago from an RBT training that I use to explain the concept of grading-for-mastery. Imagine two students in medical school. Student #1 scores an 80% on every assignment all year long. Student #2 scores 50% for the first half of the course, but scores 100% for the second half of the course and earns a 100% on the final, cumulative exam. With a traditional grading system, the first student’s score in the course is 80% and the second student’s score is 75% for the course. The next questions is…who do you want performing your open-heart surgery? I would want the student who performed perfectly by the end of the course. So in this new grading system, the final grade reflects the 100% at the end of the course, regardless of how long ittook student #2 to get there.

The part of my old classroom that I miss the most is the world map that you can see in the background of this photo. I installed two sheets of metal onto the wall and painted it with a world map. It’s magnetic and visible from all parts of the classroom. The teaching potential is endless…for the new World Geography teacher who has taken over the space.

What is your favorite way to check for understanding? I use a lot of “Cold-Calling”, and “Think-Pair-Shares” during class and an “Exit Ticket” at the end of class. I would estimate that every 5-10 minutes during class I prompt students to write down an answer to a prompt, explain it to their partner, and then I call on a student randomly to share their thoughts. It is consistently the most popular aspect of class on student surveys. And, it takes no prep, gets every student voice in the room, and gives me a ton of information about what is and isn’t “sticky” in my teaching.

At the end ofclass every day I give an “Exit Ticket.” It’s a half sheet of paper containing 2-4 questions that prompt students to explain the key concepts from the period. Sometimes I grade them, sometimes I read them and then recycle them, and sometimes I sort them into piles by right and wrong answers or other general trends to plan for a quick mini-lesson to re-teach something the following day. This practice holds me accountable to know where I’m headed every day and gives me permission to not give individual feedback if it isn’t a strategic use of my time.

The biggest perk to being in the library is that we have fantastically comfortable furniture that students can use when we’re in small group work or writing independently. It’s pretty awesome to have a couple of nooks like this and for that I’m super grateful.

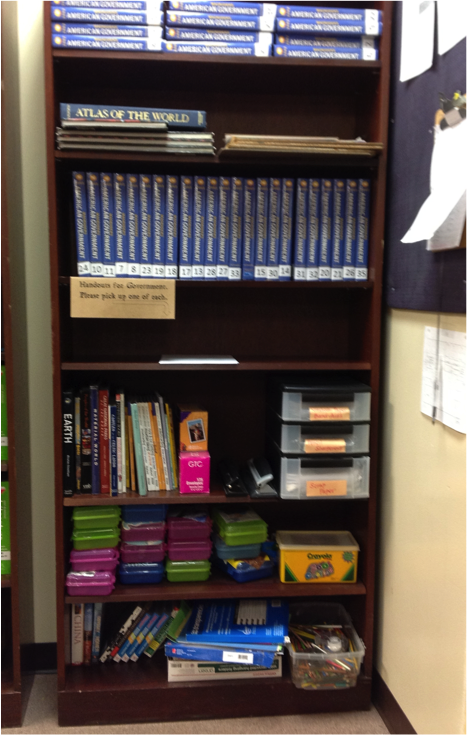

With super limited space this year, I don’t have a table for handouts, but rather an empty shelf. In addition, I leave student supplies on the same bookcase with easy access for students to get to the materials they need.

After reading Carol Dweck’s Mindset, I started teaching an annual lesson about fixed and growth mindsets to my students to help them identify both in themselves. I point to this question on the wall every time I return work to students with critical feedback or offer challenging corrections in order to support them moving more often towards embracing a growth mindset.