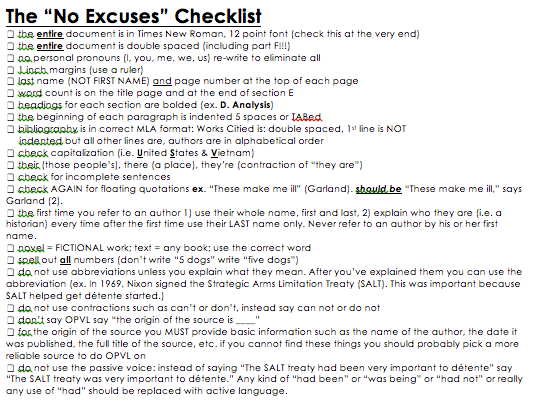

There is a moment in my teaching career I have been mulling over recently. It was Spring and I’d just passed back feedback for the big research papers my students were writing. Before students turned in their papers I passed out a “No Excuses” checklist (see below) and told them that if any of the items on the list were missing I would immediately stop reading their paper and return it to them to correct. They would then receive a consequence for having submitted a late paper.

Because I went over the items on the list many, many times most of the students who neglected items on the list were a little embarrassed when I returned it to them without my feedback and quickly made revisions. However, I remember one student who was completely outraged that I had refused to read her paper. She came to me, sobbing with furry, and accused me of hating her and wanting her to fail. “How am I supposed to get better if you don’t tell me what to do?” she yelled. I pointed out I did tell her what to do, in fact I typed it out on a list and gave her time in class to look for those changes. “Good teachers don’t let their students turn in bad papers,” she shot back, “If you really cared you wouldn’t let me fail.”

The student later apologized and even thanked me for holding her to high expectations; however, her words stuck with me. Do good teachers let their students fail? It is a question that has become central to my professional development this year and one I finally feel like I can answer. Not only do good teachers let their students fail it is actually a hallmark of excellence. Great teachers provide a safe environment – safe from a ruined GPA, safe from social ostrasism, safe from a negative self-image – where students can fail over and over again.

Even though I certainly did not execute it perfectly in the example of the irate student above, it is best practice to set students up to make classic mistakes that directly lead to a deeper understanding of the content. I could tell my students the difference between “their, there, and they’re” but I know they really learn it when they use the incorrect form, catch their own mistake and make the correct substitution. Want to see this principle in action? John Mahoney is a 40+ year classroom veteran math teacher who teaches in Washington D.C. – I am fortunate to call him my friend and colleague with the America Achieves Fellowship.

John has posted an excellent video online of a lesson he taught where students learn a concept by looking at problems and determining if they were solved correctly or not. They discuss the problem in small groups and then debrief as a class. The vulnerability students show in explaining their thinking as well as their total calm when John says “You are wrong” is a testament to the power of letting students learn from mistakes. The video is posted online here and is well worth the watch (you might have to go through a simple registration process but it is worth it! This Common Core website is a hugely beneficial tool).

Every concert violinist starts out a beginner and every pro basketball player picks up a ball for the first time at some point. Paul Tough has written about the importance of failure in building character in children both in The New York Times as well as in his book How Children Succeed (my review of that action is here), he describes how:

we have an acute, almost biological impulse to provide for our children, to give them everything they want and need, to protect them from dangers and discomforts both large and small. And yet we all know — on some level, at least — that what kids need more than anything is a little hardship: some challenge, some deprivation that they can overcome, even if just to prove to themselves that they can. As a parent, you struggle with these thorny questions every day, and if you make the right call even half the time, you’re lucky.

Next year I might make my class theme “We fail to prevail” which I know is cheesy but I think could really be a helpful way to invest kids in really struggling and engaging rigorous academic tasks. Here are some other ways you could set your classroom up for failure (in a good way):

- Reject perfection and speed: Carol Dweck in her book Mindset describes how our society idolizes doing something faultlessly and effortlessly, as if it is an inherently bad thing to actually struggle, or God forbid, break a sweat. Dweck suggests that when teachers see students who are quickly able to complete a task to perfection we should give them a more difficult task and apologize for “wasting their time.”

- Model mature mistake making: It is easy to feel like, as the teacher, we have to be perfect ourselves or we will lose credibility. Do not be afraid to apologize and own your mistakes. Students respect honesty and transparency and lord knows they scorn a faker.

- “No, this is not for a grade:” Some times the pressure of earning a grade needs to come off in order for students to relax and let themselves fail OR in order to actually try because they know the assignment isn’t simply another F to add to the stack.

- “Yes, this is for a grade:” At the same time, students need to be allowed to experience authentic failure. One bad grade will not kill them – particularly if there is a way to earn redemption by demonstrating actual mastery and improvement.

What thoughts do you have about creating a classroom safe enough to fail?